The National Basketball Association’s developmental “G League” will include an existing Mexican basketball team for the 2020-21. Could this be the portent of Minnesota losing the Timberwolves NBA franchise? For the second time?

My prediction is yes, although I take no joy in saying so. I will explain precisely why, although a history lesson is necessary.

The history of pro basketball in Minnesota

The Lakers (1947-60)

Pro basketball first landed in Minneapolis in 1947, when the defunct Detroit Gems of the old National Basketball League (NBL) were purchased and brought to the old Minneapolis Auditorium. Minneapolis Tribune sportswriter / sports salesman / huckster Sid Hartman helped engineer the deal. (It was the first of many instances where the concept of “conflict of interest” meant nothing to “legendary” Mr. Hartman.) Playing as the “Minneapolis Lakers,” the team actually won the NBL championship in their first season of play, 1947-48. The team then joined the Basketball Association of America (BAA) for the next season and won the 1948-49 championship. In the intervening summer, the NBL and BAA merged to form the National Basketball Association (NBA). The Lakers captured another championship in the 1949-50 season. Coached by John Kundla (another arrangement brokered by Hartman) and featuring George Mikan, the Lakers were clearly the dominant team of the era, winning championships again in 1952, 1953, and 1954. Awfully impressive.

The problems began when Mikan retired as a player in 1956, citing family needs and having sustained 10 broken bones during his career. The team’s performance sagged and attendance plummeted. And although Mikan returned for 37 games during the 1955-56 season, followed by a stint at coaching, this led to further failure and led Mikan to concentrate on law and business for a number of years. Losing, sinking attendance, and more financial woes continued unabated.

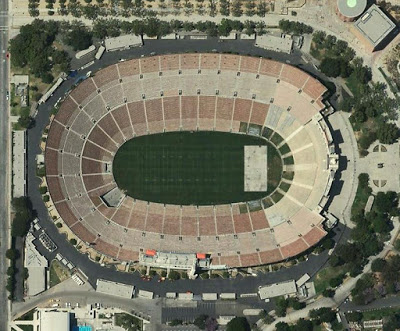

After the 1959-60 season, then-owner Bob Short moved the team to Los Angeles, becoming the NBA’s first West Coast team: The Los Angeles Lakers. It took 12 years, including the 1965 sale of the team to Jack Kent Cooke and 6.5 seasons in the old Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena, but the Lakers returned to championship form in 1972 and have never looked back.

By the way, two American Basketball Association teams, the Minnesota Muskies (1967-1968) and the Minnesota Pipers (1968-69), were both failures. The state was (and obviously still is) far more enamored with hockey, chiefly the Minnesota North Stars, who were part of the National Hockey League’s “Great Expansion” of 1967.

The Timberwolves (1989-present)

On April 22, 1987, Minneapolis business partners Harvey Ratner and Marv Wolfenson secured one of four NBA expansion franchises, to begin play in November of 1989. After spending one season in the cavernous Metrodome (built for American football, not for baseball, let alone basketball), the Minnesota Timberwolves moved into their purpose-built 19,000-seat arena, Target Center, on the other side of downtown Minneapolis. Predictably, the expansion team had trouble winning, although attendance was strong. In their third season of existence (1991-92), the Timberwolves managed to win only 15 games, losing 67 others. A long string of coaching changes fixed nothing; their records in 1992-93 and 1993-94 were 19-63 and 20-62, respectively.

In fact, when the franchise should have been in precisely an enjoyable spotlight, the 1994 NBA All-Star Game at Target Center, owners “Harv and Marv” were in financial ruin, mostly because of the mortgage for their arena. As a result, they attempted to have a public or private entity take over ownership of the arena, while representatives from San Diego, California; Nashville, Tennessee, and Bob Arum’s shady boxing outfit Top Rank from New Orleans, Louisiana all vied for team ownership.

On May 23, 1994, Top Rank successfully purchased the Timberwolves from “Harv and Marv.” “Sold Down the River” was the Minneapolis Star-Tribune‘s headline on the next morning’s front page. Some locals and basketball fans cried foul, but the overwhelming reaction from most Minnesotans generally was, “go pound sand.” Part of that apathy was touched off by the very controversial franchise transfer of the Minnesota North Stars to Dallas, Texas by non-local owner Norman Green in the spring of 1993. Minnesota’s sports fans had been betrayed, again.

However, the sale of the franchise was fraught with problems almost immediately. On June 15, 1994, the NBA’s franchise relocation committee shot down the sale, citing the absence of concrete funding sources. The league then filed suit in United States District Court in Minneapolis, basically to protect themselves. One week later, Top Rank counter-sued. Shortly after that, local businessman Bill Sexton gave up on trying to purchase of the team after eight months of effort.

(In hindsight, Sexton’s “failure” was a blessing-in-disguise for him.)

Mankato, Minnesota billionaire and former State Senator Glen Taylor succeeded in buying the team in October of 1994, but the ownership change had no impact on the team’s fortunes in the 1994-95 season; the “Woofies” were 21-61. At least the arena ownership issue was “solved” when the City of Minneapolis bought the arena in 1995, with a couple of expensive renovations that followed. Target Center remains a nice building for basketball and rock concerts.

Anyway, in the 1995 NBA Draft, the Timberwolves selected Chicago high school standout Kevin Garnett. This should have been the launch of meteoric team success; the Woofies qualified for the playoffs that season, but were quickly eliminated. Garnett proved to be the backbone of the Timberwolves for several seasons, but his new 6-year, $126 million contract in 1998 touched off a firestorm of controversy over the sheer amount of money. Meanwhile, the team still had a violently revolving roster of players and coaches, and still had not won a playoff series.

More management blundering burned the Timberwolves when they attempted to secretly sign free agent player Joe Smith to a series of one-year contracts. League commissioner David Stern found out about the rules violations (of course) and ultimately stripped the team of three first-round draft picks, fined the team $3.5 million, and suspended Minnesota-born general manager (and retired NBA star) Kevin McHale for an entire season.

Eventually, after the 2003-04 NBA regular season, the Timberwolves actually won a playoff series. Two, in fact. Woofies fans were finally able to be delirious about actual playoff success, but then, Sam Cassell injured himself doing a stupid celebratory dance. Ultimately, the Los Angeles Lakers (remember them?) disposed of the Timberwolves, four games to two, on May 31, 2004. But at least the Timberwolves, after 14 seasons, finally had some shred of playoff success. Fans hoped for more.

Even I, who had no interest in basketball, hoped that after more than a decade, the Timberwolves might have some consistent success, because when they succeed, surrounding businesses, corporate sponsors, and more have a chance to succeed, too.

The problem is that the Timberwolves have not won another playoff series since. The team went a whopping 13 seasons without qualifying for the playoff tournament. The 2017-18 Woofies got into the playoffs, but the Houston Rockets chewed them up and spat them out, four games to one. Then in 2018-19, the Woofies went 36-46 and missed the playoffs again. And after 25 games of the current (2019-20) NBA regular season, the Wolves have stumbled badly to a 10-15 record.

Aside from the tragic deaths of player Malik Sealy on May 20, 2000 and two-time head coach Flip Saunders on October 25, 2015, the history of the Minnesota Timberwolves franchise has been an unending downhill train-wreck. The team is now on its 13th different head coach and 10th different general manager.

I will bypass the idiotic behavior of some of the most disgusting characters the team has employed; you can certainly read more about Isaiah “J.R.” Rider and Latrell Sprewell on your own.

The early years of ignominy were inevitable and should be excused. It is the four years from May 22, 2009 to May 3, 2013, when former sportswriter David Kahn “served” as the Timberwolves General Manager, that this franchise was at its absolute, bottom-of-the-barrel, hideous, Cop Rock-ian imbecility. During that stretch, the Timberwolves’ records were 15-67 (tied for the worst in franchise history), 17-65, 26-40, and 31-51.

Over 30 full seasons, the “Trembling Timber-Chihuahuas” (that name credit belongs to Patrick Reusse) have racked up only those two playoff series victories in only 9 winning seasons.

The best player in team history, Kevin Garnett, had to go to Boston to experience any real success. Fortunately for him, the Celtics won the 2008 NBA championship, in Garnett’s first year with the team.

Put succinctly, the Minnesota Timberwolves franchise has been arguably the most expensive, costly, and embarrassing mistake any of the major North American professional sports leagues has ever wrought. They are, for all practical purposes, forgotten but not gone, in Minnesota.

“Long Way to Mexico”

We are now at the potential “seed-sprouting” of the turning point of Minnesota Timberwolves history.

Since November 2, 1990, the NBA has held 32 regular season games (and many more exhibition matches) outside of their home arenas in the United States and Canada. Eleven of them have been held in Mexico City. A 12th game was supposed to be played at Arena Ciudad de México (“Mexico City Arena”) on December 4, 2013, but perhaps because the Timberwolves would have been featured, the game had to be cancelled because… get this – an electrical generator began belching smoke, ruining the air inside the arena.

Clearly the NBA wants to develop new and emerging markets and audiences. And why shouldn’t they? After all, the NBA is about money and growing their audience.

Through all of this absurdity, Glen Taylor continues to own and operate the Timberwolves. Mr. Taylor is not a fool; if he ever found this franchise unprofitable and unable to operate in the black, he could have sold the team long ago. In fact, as business journalist Nick Halter reported in July of 2016, Taylor sold almost 10% of the team to New Jersey businessman Meyer Orbach, and 5% to Chinese businessman Lizhang Jiang. Halter properly notes that bringing Jiang into the ownership picture might be with an eye toward building the NBA’s overall presence in China – an effort that went badly and infamously wrong only months ago.

Then on May 1, 2019, Colombian-born Gersson Rosas became the president of basketball operations for the Timberwolves. This is not “for diversity appearances only;” Rosas previously worked in the Houston and Dallas NBA franchises, as well as for Team USA Basketball. Coming from a non-basketball fan, IMHO, Rosas seems well-qualified for the job.

And now, on Thursday, December 12, 2019, the NBA has announced that they will bring an existing Mexican basketball team into their developmental “G League” for the 2020-21 season. Los Capitanes de Ciudad de México (“The Mexico City Captains”) will be part of the “G League” for a minimum of five years. They will play in the 51-year-old, 5,242-seat Gimnasio Olímpico (“Olympic Gymnasium”) Juan de la Barrera, for now.

The very next day in another article on the NBA’s own web site, staff writer Matt Petersen trumpeted that the NBA was “doubling down on Mexico.” Petersen wasted little time getting to the most important point behind current NBA commissioner Adam Silver’s plans:

The most oft-asked question: is an NBA team coming and, if so, when?

The question behind the question was clear. What were all the regular season games, clinics and youth academies from the last few years building towards?

Silver’s answer was emphatic.

“I think it’s an important signal to the market just how important we view the entire country of Mexico and all of Latin America,” Silver said.

Put more simply: Yes.

When? It’s impossible to say, but I refuse to bet against it. In my opinion, this is now inevitable.

Like all of us humans being, Mr. Taylor is not immortal. Born in April of 1941, he is 78 years old as of this writing. He became a successful billionaire businessman not by failing to plan for the future of his estate. And while passing on the franchises to his heirs is possible, we could also reasonably assume that Mr. Taylor might choose to sell any or all of the remaining 85% of his ownership stake in the Timberwolves, the four-time WNBA champion Minnesota Lynx, and the NBA G League’s Iowa Timberwolves.

The NBA desperately wants all of its franchises to be successful, because money and income drive everything the league does. The NBA’s blockbuster expansion of their development league to Mexico City is certainly no accident. In the last six days, four NBA teams played two games in the relatively new Mexico City Arena. Both were *smashingly* successful sellouts of over 20,000. A new NBA league store has opened in Mexico City’s Polanco neighborhood.

And Rosas would seemingly have several advantages as the Timberwolves president.

Is all of this becoming clear, now?

The Timberwolves are clearly an afterthought in Minnesota. However profitable the franchise is for Mr. Taylor, the Minnesota Timberwolves are an almost useless, expensive, almost “scorched earth” stain on the overall body of the NBA.

In addition to the Woofies’ ineptitude, you must also consider the gobsmacking Minnesota Gophers basketball academic fraud scandal. The Gopher men’s program already had two ugly scandals during the 1970s and 1980s, but this one occurred right under the nose of the Minneapolis Star-Tribune‘s veteran sports reporter huckster Sid Hartman. When rival Saint Paul Pioneer Press reporter George Dohrmann‘s story exploded on March 10, 1999, just ahead of a Gopher men’s playoff game, Sid had a meltdown, as did many fans and supporters. But Dohrmann’s story held up under an NCAA investigation, and further resulted in other fraud discoveries within the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities athletic department.

Sid, far too “prestigious” or “important” to be concerned with actual news reporting nor his conflicts of interest, has never learned his lesson; he continues to shamelessly shill for Gopher sports 20 years later. In stark contrast, Dohrmann won a 2000 Pulitzer Prize for his work.

__________

Hockey reigns supreme in Minnesota. Not only do we have the NHL’s Minnesota Wild, we have not one, not two, but five universities playing NCAA Division I men’s AND women’s college hockey. Other states can only dream of having the successful boys’ and girls’ high school and junior hockey programs and tournaments we have.

Basketball is a fourth-tier sport in Minnesota, at the most. If you factor in Minnesotans who play golf, support professional and amateur tournaments, and have attended men’s and women’s major championships, and the Ryder Cup and Solheim Cup Matches, basketball might actually be a fifth-tier sport, here.

__________

Put all of the above together with the NBA’s (intelligent) addition of “Los Capitanes” to their minor league next season.

Just as billionaire businessman Stan Kroenke brought the NFL Los Angeles Rams home after 20 seasons in Saint Louis, NBA commissioner Adam Silver is working toward making pro basketball work in Mexico City.

The business indicators and recent history overwhelmingly suggest that Silver, Los Capitanes, and the NBA’s Mexico strategy will succeed. Several years of sustained business and economic success will need to occur, but I refuse to bet against any of them.

“Los Capitanes” is the beginning of the end of the Minnesota Timberwolves – and very likely “the beginning of the beginning” of what may become Los Lobos de la Ciudad de México. Mr. Taylor (and/or his executors) will eventually sell the team. The NBA will triumphantly move the franchise from a useless Minneapolis market to Mexico City. All matter of marketing, publicity, perhaps under Mr. Rosas’s dynamic management, etc., etc., will ensue.

And for basketball fans in Minnesota, all that will remain will be memories, news accounts, photographs, videocassettes and archived digital media from a bygone era.

That, and probably at least one more major future Gophers basketball scandal.